This one started, as many things do, with an audio Bible and a double-take.

I was listening to Mark 1 on the NIV and heard the familiar story: the man with leprosy kneels and says, “If you are willing, you can make me clean.”

But instead of “Jesus was filled with compassion”, which was how I remember the 1978 translation of the NIV that I grew up with, the reader said:

“Jesus was indignant.”

Hang on. Indignant? At the man? At the disease? At the crowd? At the whole mess of a fallen world? And what happened to the compassion I grew up reading and hearing?

Welcome to one of the more interesting little variants in Mark.

Two competing participles

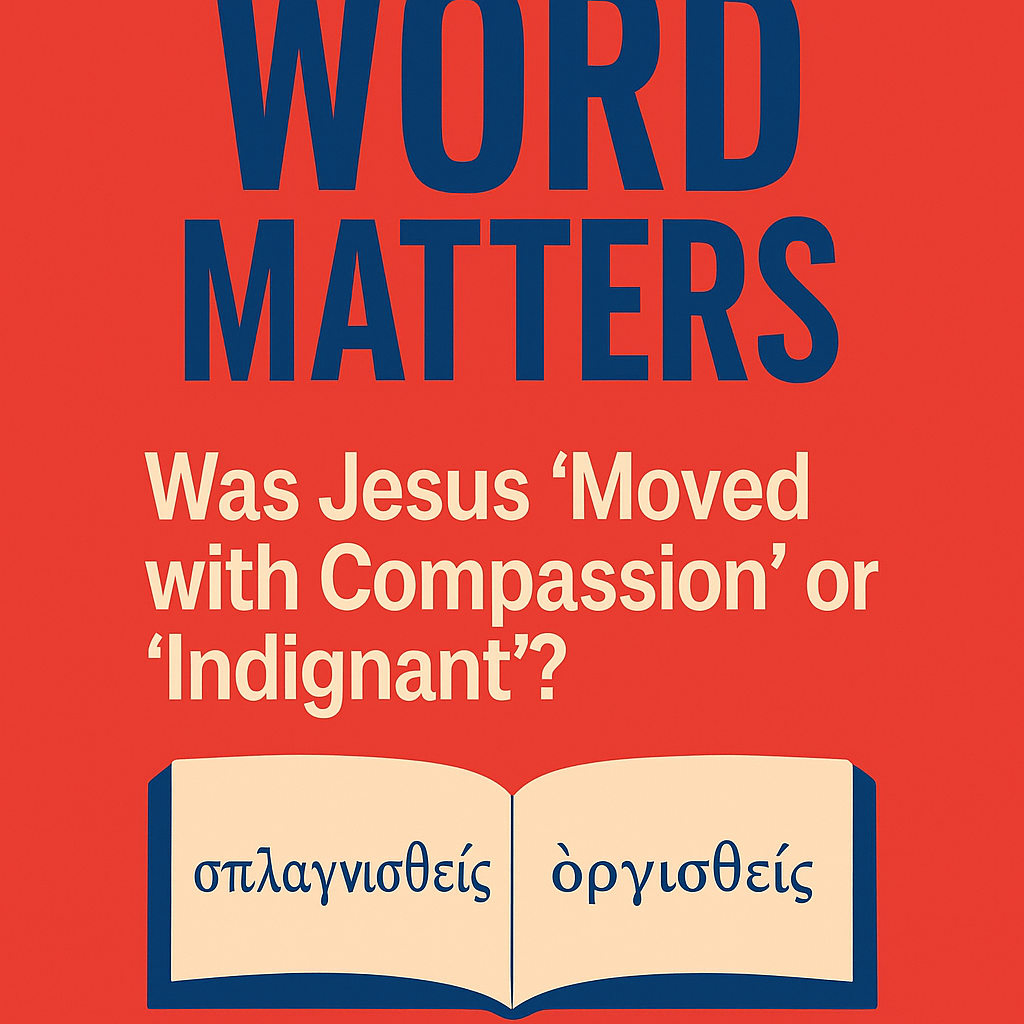

Underneath our English Bibles there are two different Greek readings in Mark 1:41:

– σπλαγχνισθείς – splagchnistheis – gloss: “moved in his guts with compassion / mercy”

– ὀργισθείς – orgistheis – gloss: “became angry / was indignant”

Both are aorist participles, both describe Jesus’ inner response just before he reaches out and touches the man.

A quick reminder from earlier in this series: these short English phrases are glosses – thumbnail sketches of the sense here, not “the one true meaning of the word everywhere”.

Who says what?

Very broadly:

– the vast majority of Greek manuscripts read splagchnistheis – compassion

– a small Western group plus some Old Latin witnesses read orgistheis – anger or indignation

Modern critical editions still print splagchnistheis in the main text and list orgistheis in the apparatus. The editors are basically saying, “We see the angry Jesus variant, but we still think compassion is more likely original.”

So how did the NIV end up with “indignant” when most Greek manuscripts say compassion?

Why NIV 2011 went with “indignant”

The NIV revision committee accepted a minority argument that goes like this (simplified):

1. Harder reading. Scribes are more likely to soften an awkward line than to make a nice, safe text more difficult. “Jesus was angry” is tougher than “Jesus felt compassion”. So if two texts disagree, human nature tells us the ‘harder’ reading is more likely original.

2. Mark likes a prickly Jesus. In this Gospel we see Jesus angry or deeply stirred: at hardness of heart, at the disciples blocking children, at religious games around the temple. “Indignant” fits that rough-edged Markan profile.

3. Context. On this reading, Jesus’ anger is aimed not at the man himself but at the whole leprous, isolating horror he is trapped in – the ravages of sin and uncleanness wrecking an image-bearer.

On that basis, they judged that even though orgistheis has much smaller external support, internally it may be the better explanation: a raw, angry Jesus smoothed into a more pious, compassionate one by later copyists.

That is why TNIV and NIV 2011 say “Jesus was indignant”, usually with a footnote such as, “Many manuscripts, Jesus was filled with compassion.”

Why many others stick with “moved with compassion”

Other evangelical scholars look at the same data and shrug in the opposite direction:

– externally, the splagchnistheis reading is overwhelmingly supported across regions and manuscript families

– internally, it is not obvious that “anger” is the tougher reading here; would a scribe really feel the need to protect Jesus from compassion?

– we also need to account for the character of the Western text, which has form for “creative” readings and expansions elsewhere

They agree that Jesus can be angry in Mark; they are just not convinced this is the verse to stake that claim on. So other translations quietly stay with “moved with pity” or “filled with compassion” and leave orgistheis in the apparatus or the footnotes.

So which way do we go?

If you are expecting a dramatic reveal here, sorry – this is one of those places where faithful, Bible-loving scholars disagree and we probably will not settle it this side of glory.

Where does that leave the ordinary reader and the preacher with a Sunday deadline?

You can trust the story either way

In both readings Jesus:

– breaks through social and ritual barriers

– stretches out his hand

– touches the untouchable

– speaks the freeing word: “I am willing. Be clean!”

– and the leprosy leaves immediately

Whatever we decide about the participle, the narrative shows both his compassion and his holy intolerance for the damage sin and uncleanness have done.

Preach the text you have, acknowledge the variant

If your congregation’s Bibles all say “indignant”, do not pretend they do not. Explain, in simple language, that some manuscripts read “moved with compassion”, most translations follow that, and the NIV committee were persuaded by the minority argument. You can sketch the two views and move on without turning the sermon into a seminar.

If your Bibles say “moved with compassion”, do the same in reverse: show that there is a small but interesting “indignant” tradition and why you are not hanging the weight of the passage on it.

Be clear what Jesus would be angry at

If you lean towards orgistheis, be clear: his anger is at the disease, the exclusion, the fallout of the fall – not at a desperate man daring to ask for help. This is righteous fury at the wreckage, not irritation at the wrecked.

Do not build a whole doctrine on one participle

Mark’s Gospel already gives you enough data about Jesus’ emotions: compassion for crowds, anger at hardness of heart, weariness, sorrow, distress in Gethsemane. Mark 1:41 contributes to that portrait, but it is not the linchpin.

Word-studying splagchnistheis or orgistheis to death and then ignoring the rest of the chapter is exactly the sort of thing this series is trying to resist.

What this variant actually teaches us

For me, Mark 1:41 does two things at once.

First, it reminds me that Jesus is not emotionally neutral. Whether he is “moved with compassion” or “moved with anger”, he is moved. The living God in human flesh is not coolly detached from human misery. He feels it, and he acts.

Second, it quietly showcases why textual criticism belongs to ordinary discipleship, not just exam papers and Bachelors of Divinity. A single little word with two possible readings:

– does not undo our confidence in Scripture

– does invite us to pay attention

– and ends up deepening our sense of Christ’s heart rather than flattening it

In the next piece we will look at another famous “word that grew a theology” – μετάνοια (metanoia – “repentance / change of mind and life”) and how a Latin gloss, poenitentiam agite (“do penance”), helped steer whole chunks of Western piety.

For now, whether your Bible says “filled with compassion” or “indignant”, hear the main thing:

The willing Lord touches the untouchable and makes them clean.